In June, my son and I took a trip to the Canadian Rockies that included Banff, Jasper and Glacier National Park, three scenic parks I had on my “to do” list for a long time. Time to “do” it. We looked forward to seeing majestic, snow-capped mountains, rapidly receding glaciers, pristine jeweled lakes and the fabled wild life. We were not disappointed.

This trip was organized by Caravan Tours. We had done other trips with Caravan and were comfortable with their itineraries, organization, motor coaches, hotels and meals. This particular tour is a popular one and sells out quickly. So, we took precautions to book early, in fact, as soon as it was announced, a wise decision as it later turned out. It was quickly sold out.

We took the Air Canada non-stop flight from Newark, New Jersey, to Calgary, Canada, the starting point of the tour. There was a heat wave in the Northeastern US during the week of our departure with temperatures well over 90 degrees F. We were looking forward to a spell of cooler weather in Canada. After landing, we took a cab to our hotel and arrived in time for the welcome and orientation briefing where we met our forty-four fellow travelers and our tour director, Graeme Hudson, who had a delightful English accent, not surprising since he had arrived in Canada from England when he was forty years old.

After the briefing we went to bed, we had an early start the next day. We soon fell into a familiar routine—leave our suitcases outside our rooms in the morning and head for breakfast. The hotel staff would transport them to our coach where they were loaded ready for us to board and set off for that day.

After breakfast we walked out to the large motor coach and met our driver Lorn, a tall, athletic Canadian with a pleasant, resonant voice. Over time we realized he was very knowledgeable about the flora, fauna, geography and history of the places we visited. He has been driving for many years, is very experienced and took good care of the coach. I have seen him washing the windows. They were spotless. Taking pictures through them was a breeze. The coach was a “kneel down” coach, that is, at the touch of a button, the front lowers itself close to the ground when we boarded or got off, very helpful for old timers like myself with creaky or replaced knees.

We drove through Calgary and saw the city highlights including the Calgary Tower, the many ornate bridges and fountains, City Hall, Wonderland and the noted Spanish sculptor Jaume Plensa’s Head Sculpture.

The city was getting ready for the Calgary Stampede, an annual rodeo held in July to showcase the area’s cowboy heritage. It is a big festival and attracts over a million visitors every year. We saw large billboards, cowboy-themed paintings and a huge tent that would serve as a beer hall. Soon we were outside the city and cruising south through Alberta’s cowboy country with vast, empty prairies—rolling grasslands as far as the eye could see. To the west this flat, green vista was broken by the foothills of the Rocky Mountains with snow still glistening on their peaks.

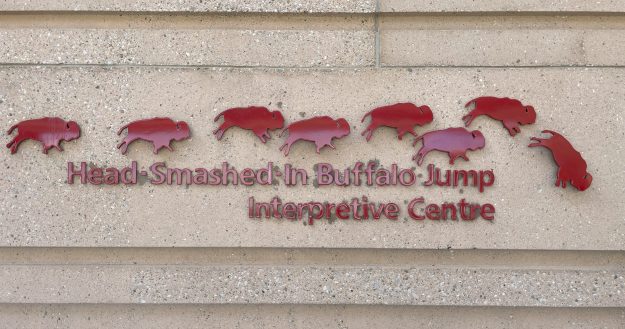

Our first stop was at the Head-Smashed-in-Buffalo-Jump, a UNESCO World Heritage site. We soon understood why. For thousands of years the Native American Plains People had hunted the buffalo (aka bison) for their sustenance. The flesh provided food, the skin was used for clothing and tent coverings. They used creative means to harvest large numbers of buffaloes by driving them over a cliff. The food they provided got the people through the unusually harsh Canadian winters. This site, one of the oldest hunting grounds, is now used as an interpretive center to explain the significance of this 6000 year-old hunting ritual of the Plains People.

Immediately, on entering the museum, we were faced with a diorama of three large buffaloes with flared nostrils and rolling eyes poised on the edge of a tall cliff. I took in the scene, a preview of what was to come.

Our guide ushered us into the auditorium to see a short film of such a buffalo hunt. The prairie, before the arrival of the White Man, was teeming with millions of buffalo. The Blackfoot (Blackfeet in the USA, an Indigenous North American tribe) used their knowledge of buffalo behavior and the topology of the area to their advantage.

Blackfoot legend has it that one boy wanted to witness the scene of hundreds of buffaloes plunging over the cliffs. He stood under the shelter of a ledge watching the scene. The hunt was unusually good that day. Soon, the huge carcasses had him trapped. Later, when the men and women arrived, they found his head smashed in by the weight of the bodies. Hence the name—Head-Smashed-In-Buffalo-Jump.

After the movie, I climbed a few flight of stairs and left the building on a trail that took me to the cliffs shown in the picture above. This was the buffalo-jump spot. My mind went back six thousand years. I sat on a rock and fell into a reverie. Everywhere I looked there were buffaloes grazing peacefully. Mothers nursed their young and big bulls kept watch over their harem and fended off interlopers. Hunters, working diligently for the past few days, had quietly separated a few hundred animals from the rest and forced them into a narrow corridor with strategically placed stone cairns to prevent their escape. It was time for the hunt.

Early in the morning, the lead hunter consulted the Shaman and donned the hide of a buffalo calf. Staying close to the ground, he gave the plaintive call of a lost calf. The herd’s instinct is to bring it to safety and therefore start following the calf. The hunter, still calling, slowly led them to the cliff’s edge. There were grizzled veterans in the herd who sensed the danger and tried to turn back but other hunters dressed in wolf skins harried them at the flanks forcing them to keep moving forward. Progress was slow. The men trod carefully—no one wanted to spook the herd or land under the hooves of a one-ton buffalo running scared. The hunt was a team effort; well planned, coordinated and executed, a formidable capability that allowed humans to eventually dominate other species.

At the last moment (and that required courage, experience and split-second timing), the lead hunter raced off to the side while the others surged forward shouting and waving branches and flaming torches scaring the buffaloes into a stampede over the edge. The air reverberated with the thunder of hooves, terrified bellows and the crash and crunch of heavy bodies landing on the ground and on each other, sixty feet below. The small herd soon disappeared over the side as the hunters danced with jubilation on the cliff top as the dust slowly settled. They now had enough food to last the winter.

Below the cliff, in the camp, there was much work to be done. The women and children speared the animals still alive and started the process of butchering. The carcasses were skinned, the hides scraped and spread out. The flesh was cut into strips and laid out to dry or ground with fat and berries into pemmican, the calorie-rich food that was a staple of the indigenous diet. The women sang as they worked, happy in the thought there would be rich meat to eat and they would be warm in their tepees as the icy winter winds howled from the north and the mercury dropped to -15 degrees Centigrade (2 degrees Fahrenheit). I woke from my reverie realizing I had just replayed in my mind what I had seen in the movie. This hunt occurred at this very jump-spot.

I looked around at the surrounding empty prairie and the mountains to the west. What must it have been before the advent of the white man, I wondered.

I reentered the museum and saw more exhibits. There was a pile of buffalo skulls. The animals were ruthlessly slaughtered for sport on an industrial scale in the 18th and 19th centuries. Sometimes the meat and tongues were taken for food and the hides to make winter coats. Oftentimes the carcasses were just left to rot in the wild. I saw a buffalo-skin coat on exhibit. By the late 19th century, the animals were on the brink of extinction, only a few hundred were left in the wild. Mercifully, their numbers have increased but are nowhere near what they were before.

I got back on the bus in a thoughtful mood. This was a way of life long gone, the way of the passenger pigeon and the dodo. Nothing would bring it back.

I remembered the lines of the famous poem Morte d’Arthur by Lord Alfred Tennyson:

“The old order changeth, yielding place to new..”

Such is life.

Our next stop was the Kootenai Brown Pioneer Village where we would glimpse another old way of life and have dinner. That would be in the next post.

To be continued. Next post: My Canadian Rockies Part 2: Kootenai Brown Pioneer Village.

Pingback: My Canadian Rockies Trip, Part 2: Dinner at Kootenai Brown Pioneer Village | Ranjan's Writings